On 1 July, compulsory superannuation turned 25. It's an anniversary that Australian workers have good reason to celebrate, because the vision and foresight of the then Labor government and trades union leadership has developed into a world class system that has served fund members exceptionally well. The industry should be underlining that message by presenting a united endorsement of the positives, rather than undermining confidence through the public airing of internal disagreements.

The success of superannuation can be measured in different ways, but most important are the investment returns that, over time, serve to grow fund members' nest eggs. Growth options (61 – 80% growth assets) are by far the most commonly used because they are the default options for the majority of members. They are long-term propositions and they set their risk and return objectives accordingly.

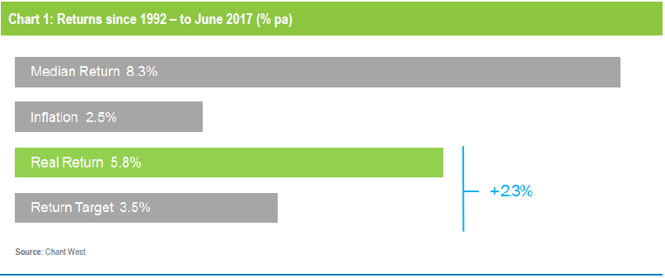

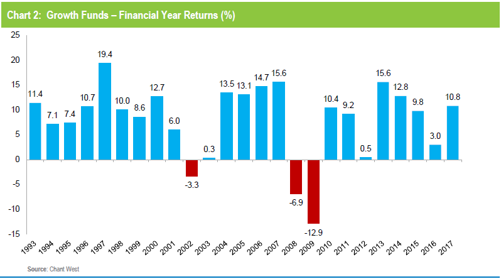

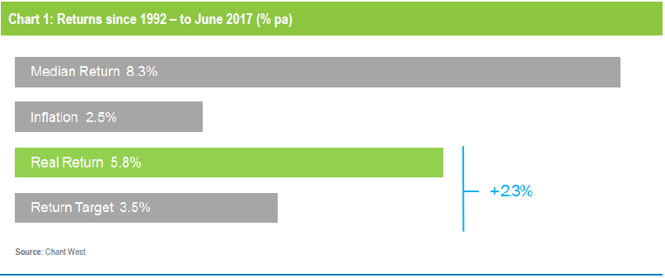

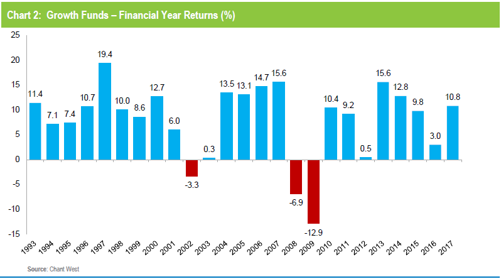

The typical performance target is to deliver a real return of 3 to 4% per annum net of fees and taxes (say 3.5% on average) over rolling five year periods. Risk objectives are generally expressed in terms of the likelihood of negative returns. Typically, funds aim for no more than one negative year in every five. With 25 years of data now available, we have plenty of evidence by which to judge funds against these targets.

Looking first at the all-important performance record, Chart 1 shows that the median fund has easily surpassed the return target. Over an extended period that includes the worst financial crisis that most of us can remember, funds have returned 5.8% above the rate of inflation. That's a very substantial boost to the real wealth of their members.

Has that strong performance come at the cost of higher than expected risk? No, it has not. As Chart 2 shows, there have been just 3 negative years over the past 25, including two in the depths of the GFC. At an average of about one in 8 years, that is well within the risk target.

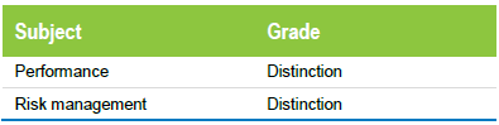

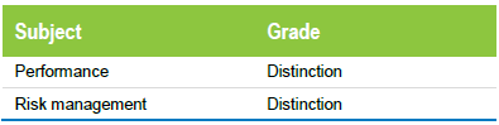

The investment report card, therefore, looks like this.

Other factors come into the appraisal, of course. In our view, the most important of these is member services. If a fund can engage with its members, inform, encourage and guide them to make appropriate decisions at crucial times, then those members will maximise their eventual nest eggs and get the best value they can from their superannuation.

We believe funds have generally done well on this score, and the leaders in member services have done exceptionally well. They have a strong focus on adequacy, and have developed sophisticated ways of showing members how they are tracking towards a comfortable retirement. They have become adept at using data analytics to understand their members better than ever before. They use modern technology and a range of communication channels to get personalised messages, or ‘nudges’, to individuals at the right time and in a way that produces the best chance of a positive response.

Added to this, some retail funds are leading the way on convenience. By integrating members' superannuation with their other financial activities, such as banking, they are helping to make superannuation less remote and more relevant to consumers' everyday lives. That convenience needs to be balanced, of course, against the investment outcomes those retail funds are likely to deliver.

No evaluation of a financial product would be complete without some comment on security. Given the vast amounts of money involved, mainstream superannuation (Trio notwithstanding) has been remarkably scandal-free over the past 25 years. This comes down to the governance of the funds themselves and the way in which the whole industry is supervised and regulated. The message for consumers is that, as far as any investment can be, superannuation is safe.

Disunity is death

Any other industry, with this sort of track record, would be united in celebrating its strengths, selling its message and gaining the maximum positive publicity. The sorry fact, however, is that public perception of the industry is far from positive. Its achievements are largely overlooked, and instead it is perceived as greedy, inefficient and conflicted.

Much of the blame for this lies within the industry itself, with different factional elements – one in particular – seemingly obsessed with airing their differences in public. The media, of course, is far more interested in reporting the internal conflicts rather than the big picture of a highly successful industry that is serving the community well.

The problem is exacerbated by the industry's response to the endless stream of external reviews, which misguidedly focus almost exclusively on fees. What the industry should be doing is presenting a united front and pointing out that the proper measure of success is the net return that the member enjoys, not the fees incurred in getting there. Instead, the competing factions just take the opportunity to lob more propaganda grenades at each other – again, all in the public arena. No wonder consumer sentiment towards superannuation is so poor.

Not all funds are equal

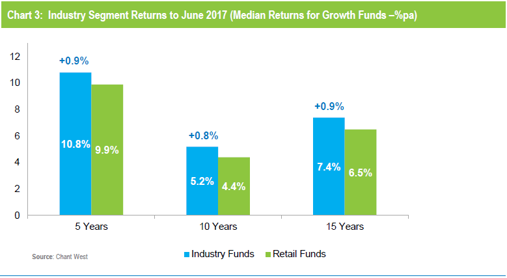

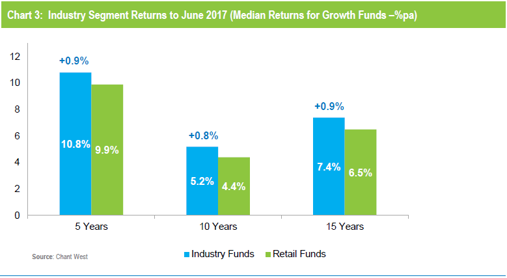

Having looked at the big picture, we will now return to the subject of investment and look at some of the factors that have shaped the way funds have performed over the past 25 years. The first and most obvious conclusion from our data is that industry funds, as a group, have consistently outperformed retail funds, and by a significant margin.

While our data goes back 25 years, the universes for the two segments are too small in the early years to make meaningful comparisons over that full period. We can, however, make meaningful comparisons over periods that still constitute the medium and long term, and Chart 3 compares industry funds and retail funds over 5, 10 and 15 years.

Given that both groups have access to the same investment markets and, arguably, similar investment resources and talents, how do we explain the performance differential?

The performance we report is net of investment fees, so one might think that differences in fees would play a part. Do lower fees lead to higher net returns?

The answer is no – in fact the opposite. The investment fees incurred by industry funds have been, and still are, significantly higher than those incurred by retail funds (0.66% pa versus 0.56% pa). That is due to the fact that industry funds have been long-term investors in unlisted assets, primarily property, infrastructure and private equity. Industry funds on average have 20% of their growth options allocated to these asset sectors compared to 5% in the case of retail funds. These assets, by their nature, are relatively expensive to manage and so entail higher fees.

We are not suggesting that higher fees lead naturally to higher returns. Rather, we would say that how you invest is all-important. If investment in high quality unlisted assets is likely to result in superior risk and return outcomes for members, then surely the higher investment fees are justified.

There are philosophical and practical reasons why industry funds have been such strong supporters of illiquid, unlisted assets. From the earliest days of compulsory superannuation it was attractive for them to be able to point at physical assets and say to their members "You own that".

Over time, the illiquidity premium also played a part in that these unlisted assets performed rather better than their listed counterparts. Also, the fact that these assets were valued relatively infrequently meant they were not susceptible to the everyday volatility of listed markets.

Another key factor is that, compared to retail funds, industry funds have always had more certainty about their future cashflows. This stems from their status as default funds in so many Awards, meaning they could rely on a steady flow of Government-mandated compulsory contributions.

With the knowledge that their liquidity needs would be met from these ongoing inflows, they were free to invest in illiquid assets knowing they did not run the risk of becoming forced sellers.

92% of industry fund inflows come from compulsory Superannuation Guarantee contributions, compared with just 68% for retail funds. This relative advantage is unlikely to disappear, in our view, regardless of any changes to the default fund regime. Our experience is that employers are generally very satisfied with the funds they are contributing to now, and have no reason or incentive to change those existing arrangements.

Outsourcing – now everyone can be a wholesale investor

On the subject of employers, it is important to note the influence that outsourcing of corporate super has had in shaping the Australian market.

From the mid-1990s we have seen a transformation as, one after another, medium and large employers decided that running an in-house superannuation fund was an inefficient distraction from their core businesses. The value proposition offered by commercial master trusts and, more recently, industry funds has been compelling. As a result, the vast majority of medium-sized and large employers have outsourced their superannuation.

APRA data does not go back as far as the 1990s, but in June 2001 APRA recorded over 3,000 stand-alone corporate funds. By June 2016 there were just 30. (Source: APRA publications)

Interestingly, this is in stark contrast to comparable countries such as the US, the UK and Canada where most employers have clung on steadfastly to their in-house funds, many of which are defined benefit in design.

The Australian system is far more efficient and has been great for employees because, as members of these very large pooled vehicles, they benefit from economies of scale. In effect, no matter how small their accounts, individual members of Australian superannuation funds enjoy the advantages of being wholesale investors. This is one reason why we argue that, contrary to the stance taken by various reviews, enquiries and 'think tanks', the Australian superannuation market is in fact highly competitive at the consumer level.

Turning our attention from the past to the future, let us now make some observations and predictions of where we see the industry heading over the next 10 years.

The inexorable rise of the mega funds

Firstly, we expect the industry to become increasingly dominated by a relatively small number of very large industry funds – the 'mega funds'. At the same, time we expect many smaller industry funds will cease to exist, and that retail funds will have to work hard to remain relevant.

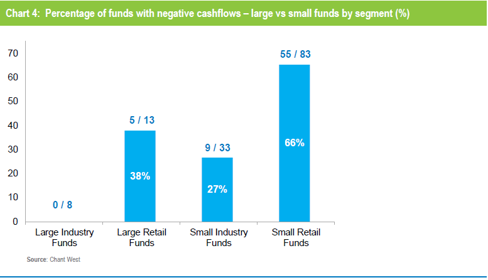

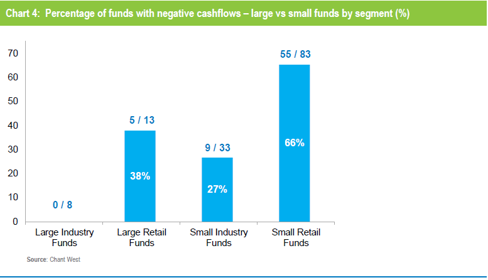

We have already seen that industry funds benefit most from the flow of SG contributions, and cashflows tell us a lot about which funds are likely to prosper and which will struggle. Chart 4, which is sourced from APRA fund level data for FY16, illustrates the cashflows for large and small funds, showing industry funds and retail funds separately. By 'large' we mean funds with assets of $10 billion or more.

Of the 8 large industry funds, all were cashflow positive. There were 13 large retail funds and, of those, 5 had negative cashflows. The pattern is similar among the smaller funds. Nine of the small 33 industry funds (27%) were cashflow negative, while the figure for small retail funds (which include some closed legacy products) was a worrying 55 out of 83 (66%).

What this suggests to us is that there will be further consolidation in the industry funds segment and that many retail funds, especially the smaller ones, will simply cease to exist once the barriers to transfers out of legacy products are removed.

The consolidation of MySuper products, in particular, will be driven in part by APRA's proposed outcomes test, which requires trustees to assess their funds annually to determine whether the outcomes they deliver are promoting the best financial interests of their members.

The Productivity Commission review, which is looking into alternative models for allocating non-choice members to default MySuper funds, will also have an influence. One of the criteria the Commission is applying is members' best interests (which, incidentally, we believe should be the over-riding consideration). Our view is that there are too many MySuper products in the market that are sub-scale, charge high fees and do not have the ability to provide the quality of service or investments necessary to qualify as default funds. It will be hard for them to survive if a members' best interests test is applied rigorously.

While many of the smaller funds will be weeded out, we can see the larger industry funds doubling in size over the next 5 to 7 years – and in the process dominating the industry. These mega funds will use their scale to drive efficiencies, in some cases by bringing more investment management (and, perhaps, other functions) in-house. They will have access to massive direct investments that are well beyond the reach of smaller funds. And, they will have the resources to develop ever more sophisticated services to help members take positive actions to drive better retirement outcomes.

So we see a more streamlined industry, with the major players having the scale and resources to take on the challenges that lie ahead. The most important of these is the demographic shift which will see retirees emerging as the dominant member category – at least in terms of assets.

The challenge for the industry is to develop retirement products (or CIPRs) that address the shortcomings of the current account-based pensions by including a longevity component for members who need some protection against outliving their assets. The new products will need to be sophisticated without becoming overly-complex, and they will need to address retirees' key requirements which are:

- reliable income

- risk management (especially investment risk and longevity risk)

- flexibility to edal with changing personal circumstances

Alongside these new products, funds will need to develop specialised services for their retiree members such as pension calculators, streamlined advice services and regular financial health checks.

There are other challenges ahead that relate mainly to the non-profit segment, including industry funds. One of these will be a renewed focus on fees once ASIC's Regulatory Guide 97 (RG97) comes into operation. The new disclosure rules will make these funds appear more expensive than they do now, even though this will have no impact on members. Perception is as important as reality, however, and they will need to work hard to keep the focus on what really matters, which is the net return that members actually receive.

Finally, to advice. The non-profit segment has been a force for good in this area, especially in driving the case for the removal of commissions and for engaging with the financial planning industry in a way that delivers advice services to the greatest number of members, not just those who can afford to pay for it.

The interaction between member services and advice will continue to evolve and, as it does, it will need to recognise that members' superannuation does not exist in isolation. The tightening of contribution and benefit limits, together with changes in the income tax system, will see an increasing number of people holding investments inside and outside superannuation. This will call for a more holistic approach to advice, and the challenge will be to deliver that in a practical and affordable way. Technology is set to be the great enabler.